[There's no little irony attached to finding out that my access to the web was throttled back by the ISP to 64kb/s (!) at exactly the same time as I'm piecing together beached whale images (from screencaps). A further bittersweet edge involves the transfer speeds and monthly broadband allowance for the service having actually increased in the previous month. One leads to the other of course: greater access begats an itchy trigger finger, more prone to click on video links that would ordinarily be avoided. My own 'beached' status is set to continue for the next ten days, so some truncated posts - as this one essentially is - may appear. At least I have a store of locally saved material from which to sample, so it's just the uploading pain that will be the limiting factor. In any event...]

While looking around the new North Holland Archive site, I happened upon the above beached whale engraving, made by Jan Saenredam in 1602 (this particular print was published in 1618). Here is the direct link to the zooming page. The title is recorded as: 'Illustri generoso Ernesti Comiti de Nassau. fortissimo Horoi, et Belgicae Liberta.is vindici acersimo D. suo clementissimo hoc monstrum [...] monstro so ho faculo D.D.D. J. Saenredam'.

This elaborate illustration conveys a profile of allusions beyond the mere narrative of the whale's beach landing. It belongs to a narrow genre of disaster allegories - of which Saenredam's print is perhaps the finest example - that found a receptive audience, chiefly in the 17th century.

Beached whales were regarded as significant phenomena, not because Early Modern proto-environmentalists galvanised a populist empathy for so striking and unusal a loss of life, but because beachings were a part of the folklore, seen as bad omens and associated with disasters and tragedies. Of course, hindsight offers both the superstitious and artist alike an opportunity to indulge in historical revisionism, so that a causal link back from a series of tragedies could be established to the rare appearance of such a great sea 'monster' on land.

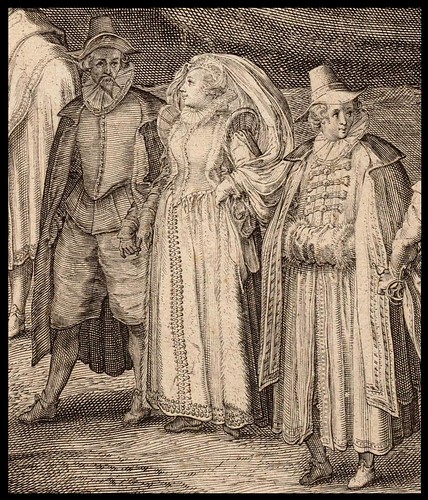

Saenredam presents the dominating scene with a journalist's eye for reporting. The main character, our sperm whale, did actually wash ashore in December 1600 in the vicinity of the towns of Beverwijk and Wijk aan Zee* and Saenredam did definitely visit the location. Ernst Casimir, Count of Nassau-Dietz and hero of the war against Spain, appears centre stage with plumed hat in front of the whale, his back to us, armed with a handkerchief to protect his refined sensitivies against the beast's odour (he visited the scene two weeks after the whale became stranded). He is accompanied by an entourage who are recorded in fine detail (the single finger 'hand-hold' between one of the couples is a delicate touch: the last image detail above).

People are inspecting the carcass and the blow hole as the townsfolk understandably stream down to the shoreline from surrounding hills and a large crowd gathers to revel in the momentous occasion. In the foreground, men stride to work carrying whale axes on poles. The artist himself appears in the scene, just below the whale's jaw, where he draws the spectacle behind a cloak windbreak, using a barrel for support. Perhaps the scene has been a little embellished to give prominence to the dignitaries, but otherwise it all appears fairly natural and not out of keeping with what one would expect to see.

The upper third of the print is a different story entirely. In a series of slightly obscure vignettes, Saenredam alludes to other circumstances that are associated with or thought to be attributable to the whale's appearance on the coast. In the far background we have both solar and lunar eclipses which occurred shortly after the whale's appearance and, like comets and other irregularly occurring natural phenomena, were seen by contemporary observers as harbingers of doom. An unhappy face has been caricatured onto the moon(s).

An angel bearing the coat of arms of Amsterdam, watched over by the ominous looking father time, is shot by death and falls from the sky, and may represent the epidemic of plague fatalities in the capital in the first couple of years of the 17th century. In the cartouche below the lion, the cartographic wind symbol can be seen blowing the land away in reference to an earthquake that occurred at the beginning of 1602. The latin verse at foot of the print is by the humanist poet, Dirk Schrevel, and although I can't read it, phrases like 'mortalibus omen' and 'monstro portenditur' appear in keeping with the overall gloom of the imagery.

The print holds a further dimension of interest because Saenredam was a student of the great Haarlem engraver, Hendrick Goltzius, whose 1598 depiction of a beached whale established the form as a legitimate artistic subject. Goltzius misinterpreted the animal's appearance however, believing that the lateral fin was actually an ear, which he sketched as more stunted and closer to the head than is true. That same stylised approach appears in the image immediately below by Jacob Matham, the stepson of Goltzius. Although Saenredam would have seen the Goltzius/Matham engravings, his own original version turned out to be an improvement over his master's approach.

Spaightwood Galleries have a biography and selection of prints by Jan Saenredam.

Otherwise, information for this entry was gleaned from the North Holland Archive, Rijksmuseum, MoMA and British Museum Prints database (origin of the Matham print).

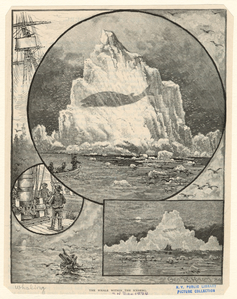

I had hoped to retrieve a few more disaster prints - relating specifically to the omen-like genre - from around the traps but the current bandwidth problem has dampened my enthusiasm. Instead, I've included a few related images from NYPL, who thankfully allow hotlinking to their smaller images these days - click through on those to get to larger versions at the host site. The final print below is particularly odd: a whale entombed in an iceberg!! I looked high and low using all permutations of search terms I could muster without finding any information. I conclude that this is a pre-photoshop hoax or shaggy sea tale.

"The beached sperm whale on the shore near Beverwijk; the whale is surrounded by diminuative figures and there is an encampment near the dunes; a dog stands on the back of the whale and a boy crawls into the gaping mouth; in the foreground a food seller approaches a finely attired couple. 1601." {by Jacob Matham}

[In other words, although this print is meant to be the same beached whale as Saenredam's, it was actually modelled after the inaccurate version by Hendrick Goltzius from 1598.]

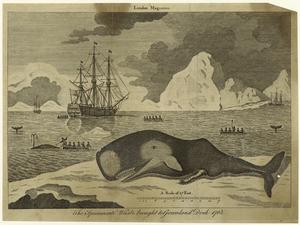

'The Spermacæti Whale to Greenland dock 1762'

IN: London Magazine

IN: London Magazine

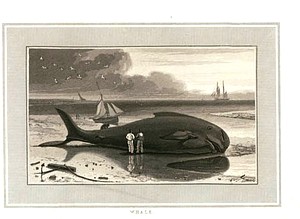

'Balæna Mysticetus'

IN: 'Interesting Selections from Animated Nature', 1807-1809.

IN: 'Interesting Selections from Animated Nature', 1807-1809.

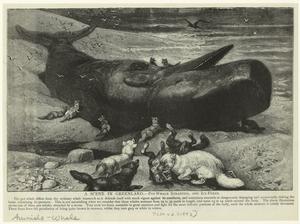

'A scene in Greenland - Pot-whale stranded, and ice-foxes'

IN: 'The Picture Magazine', 1893-1896.

"The pot-whale differs from the ordinary whale inasmuch as it defends itself with much vigour against its assailants, and sometimes succeeds in dangerously damaging and occasionally sinking the boats containing its pursuers. This is not astonishing when we consider that these whales measure from 25 to 35 yards in length, and some 13 to 14 yards around the body. The above illustration shows one of these pot-whales stranded by a storm. Very soon ice-foxes assemble in great numbers and fight for the most delicate portions of the body, until whole monster is totally devoured. These foxes have the peculiarity of being quite brown in summer, whilst they turn grey or white in winter."IN: 'The Picture Magazine', 1893-1896.

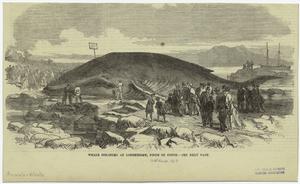

'Whale stranded at Longniddry, first of forth.'

IN: Illustrated London News, 1842.

IN: Illustrated London News, 1842.

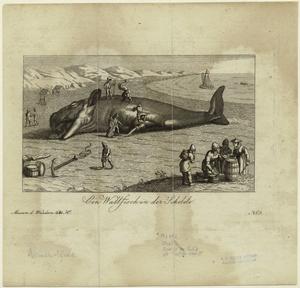

'Ein Wallfisch in der Schelde'

"Whale caught by 1603 at Dutch coast" (written in margin)

IN: 'Museum des Wundervollen..' by J Bergk, published 1869.

"Whale caught by 1603 at Dutch coast" (written in margin)

IN: 'Museum des Wundervollen..' by J Bergk, published 1869.

Arents Cigarette Card, 1920s

Caption: 'The whale within the iceberg'

by Geo. R Halm, 1884.

by Geo. R Halm, 1884.